Lessons Learned the Hard Way in Grad School (so far)

Things learned the hard way, conveyed here so hopefully you can learn them the easy way |

“Success is the ability to go from failure to failure without losing your enthusiasm.” —Winston Churchill

“Failure is only the opportunity to begin again, only this time more wisely.” —Henry Ford

“If we knew what we were doing, we wouldn’t call it research.” —Albert Einstein

Why I Wrote This

Struggle, failure, and sometimes feeling out of your depth are all inherently part of the PhD experience. These are often also accompanied by impostor syndrome, or the feeling of being inferior to those around you and a ‘fraud’. Something I find odd is that the existence of impostor syndrome is common knowledge by now, and yet just knowing of it is not enough to avoid succumbing to it. Likewise, knowing that facing failure is a universal trait of succesful people (as indicated by the quotes above) does not automatically make doing so yourself easy.

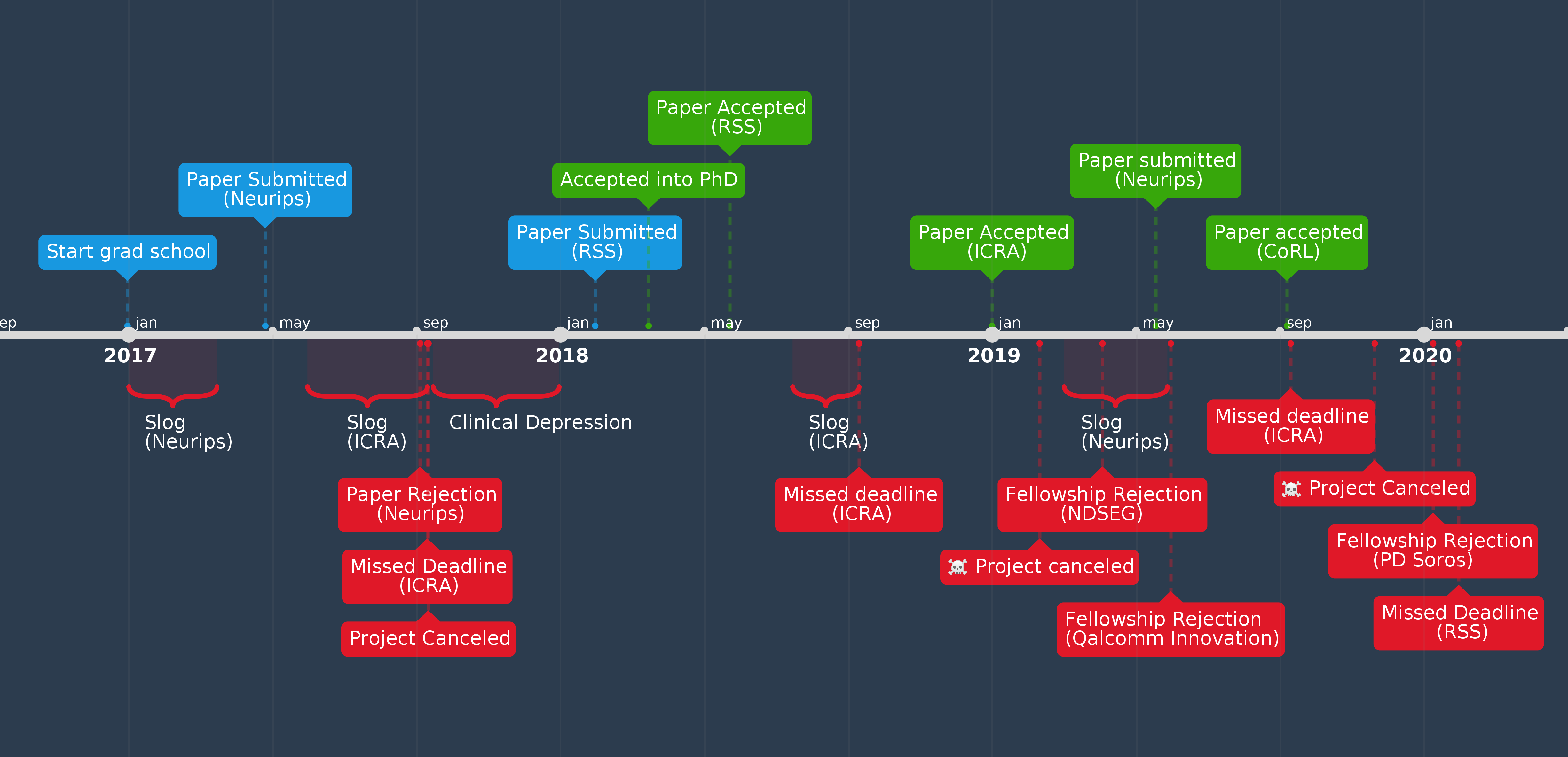

So, with a few years of grad school and many failures now behind me, I decided it would be nice to try and help some of my fellow students with these things. But given reiterating things we already know seems ineffective, I decided to take a different tact: just put my record of failures out there, so others facing similar struggles can objectively know they are at least no more an impostor than I am. And so I did, with the following video:

This post is an addendum to that, summarizing the main non-obvious lessons I took away from these failures. You can either read the below text, or watch this follow up video in which I convey what is written in the text, or both:

The Lessons

1. Test your ideas as quickly and simply as possible

Research involves a lot of debugging and trying to pinpoint why things are working (is your code buggy, or is the idea itself wrong). One easy to agree with but hard to internalize practice is to construct contrived scenarios in which you know your idea should work, so that you can ensure the code is not a problem. In other words, construct sanity checks, such as for instance if you are working on object recognition, start with a synthetic dataset of simple geometric shapes that simply has to work.

With my first project at Stanford, I did not realize to do this until after testing my code on the real task, and starting with the sanity check instead might have saved a good deal of time. This has been an essential go-to practice for me in every project since.

Neat thing from a while back: visualization of an RL agent's policy globally (in many states) while doing rollout.

— Andrey Kurenkov 🤖 (@andrey_kurenkov) February 11, 2020

Would be cool to see more like it, since shows if the agent is optimal or not and how much it generalized.

Should be fairly doable in Atari or 3D robotics envs... pic.twitter.com/sD70b6ydJJ

2. Persevere, but also pivot

One of the basic frustrating things with research is that perseverance is essential, but so is recognizing that something is not going to work and rethinking your approach. So, which should you do when you idea is not working, persevere or pivot? Both – persevere for a while, try to see more clearly why things are not working and whether they might work, and move on if they don’t.

But moving on need not result in losing all the wrong you’ve just done. Hopefully, you had good reason to believe your idea was good in the first place, and it not working can yield a different but related direction to explore. This was the case for me with my second scrapped project; the next major research project I did was directly inspired from the struggles of that scrapped project. Likewise, the project I am currently focused on acquired its focus only after months of things not working.

So, keep an eye out for the insights to be found in failure.

3. Focus on one or two big things at a time

One of my weaknesses as a grad student is a tendency to want to multi task and take on many side projects (as evidenced by the above youtube video and the text you are reading now). Some amount of exploration and side projects are of course not bad – personally I think more AI researchers should engage in science communication – but it’s easy to overdo it. In particular, at least as a junior PhD student having more than two research projects going at a time (importantly, with one in the implementation phase and one more in the ideation phase) is a good recipe for at least one of those projects dying off.

A related notion is ‘ideas are cheap, execution is everything’. That is to say, ideas are not worth much without execution to hone and actuate them (of course, advisors not directly writing code but suggesting ideas and being in the loop of execution is still invaluable). This is important to remember when you have a cool new idea and are tempted to get efforts on it going despite already having some projects in flight; if you don’t have the bandwidth to execute the idea the best thing is to wait.

Legitimately one of the best insights I've internalized after years of doing research is the old classic - "ideas are cheap, execution is everything" [not quite everything, we still need cool ideas, but y'know] https://t.co/9JK5tDhCKw

— Andrey Kurenkov 🤖 (@andrey_kurenkov) January 30, 2020

My suggestion to people who like side projects and multi tasking, like me: learn and embrace patience. The ideas that really excite will stick with you, and if you are patient there will come a time when it is strategically smart to go ahead and execute them.

4. Find a good team, and be a good team player

I intentionally avoided focusing on my successes in grad school in the above video, but thankfully I have had a few of those too. And every time I have succeeded, it was because I had great mentors and fellow PhD students working with me on whatever we were doing, and the success was really not my own but the team’s.

Unfortunately, such a team dynamic does not necessarily come about by itself; research can sometimes be a lonely endeavour, with you toiling away primarily by yourself with occasional feedback. For a largely applied discipline with a lot of implementation effort (such as AI), I really don’t think working in such a mode is ideal. So, if you do find yourself in such a spot, proactively trying to find people to work with might be a good idea. Personally, I’ve found working with both post-docs (who can be more hands-on than most advisors) and one or two fellow grad students (who can get their hands dirty alongside you) to be very helpful.

But even if you find people to work with, that does not mean things will be easier automatically. Effective teamwork is a tricky thing (so much so that I wrote up a little summary of the main things to do and not do), and it’s up to you to be mindful of how things are in terms of team dynamics. For the last few times that I put significant amounts of work into efforts that were in the end scrapped, I would say the main cause was me going at it too much by myself and not getting enough of a team consensus around one direction. So, remember to not be too much of a lone wolf and to be an effective communicator.

5. Maintain Your Health

No matter how much of a tough skin you have, research is not meant to be easy and sometimes things will get tough. Unfortunately, in grad school it’s all too easy to let yourself completely give up on work-life balance at such times and go full on tunnel vision mode. Sometimes going all in on research leading up to a deadline is not a bad idea, but you have to be cognizant of whether you have enough physical and emotional energy for it and at all costs avoid burn out. And the fact is, burn out, anxiety, and even depression are things you may have to face at some point.

So, it is all the more important to practice and get good at relaxing (weird as that may sound). Seriously, knowing yourself well enough to have good healthy ways of dealing with stress is essential and often not praised enough. Personally, when I was dealing with clinical depression I leaned on a whole set of activities that kept me going: reading on my porch most evenings, watching a ton of fun anime, going to kickboxing classes, cooking, and where I was really down playing some really absorbing video games (Civ 5, I’m looking at you).

These days I am really big on napping, but i’m also a big believer in meditation and of course the benefits of excercise and a good support network cannot be overstated.

Conclusion

So there you have it, my main lessons gathered so far. This is not all the advice I think is useful for taking on grad school, but it is the advice I had to learn the hard way and that I think is at least somewhat interesting. Feel free to comment with your own thoughts on this topic!

Previous Post | Next Post

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.