A 'Brief' History of Game AI Up To AlphaGo

The start of the story of how humanity made computers good at Go |

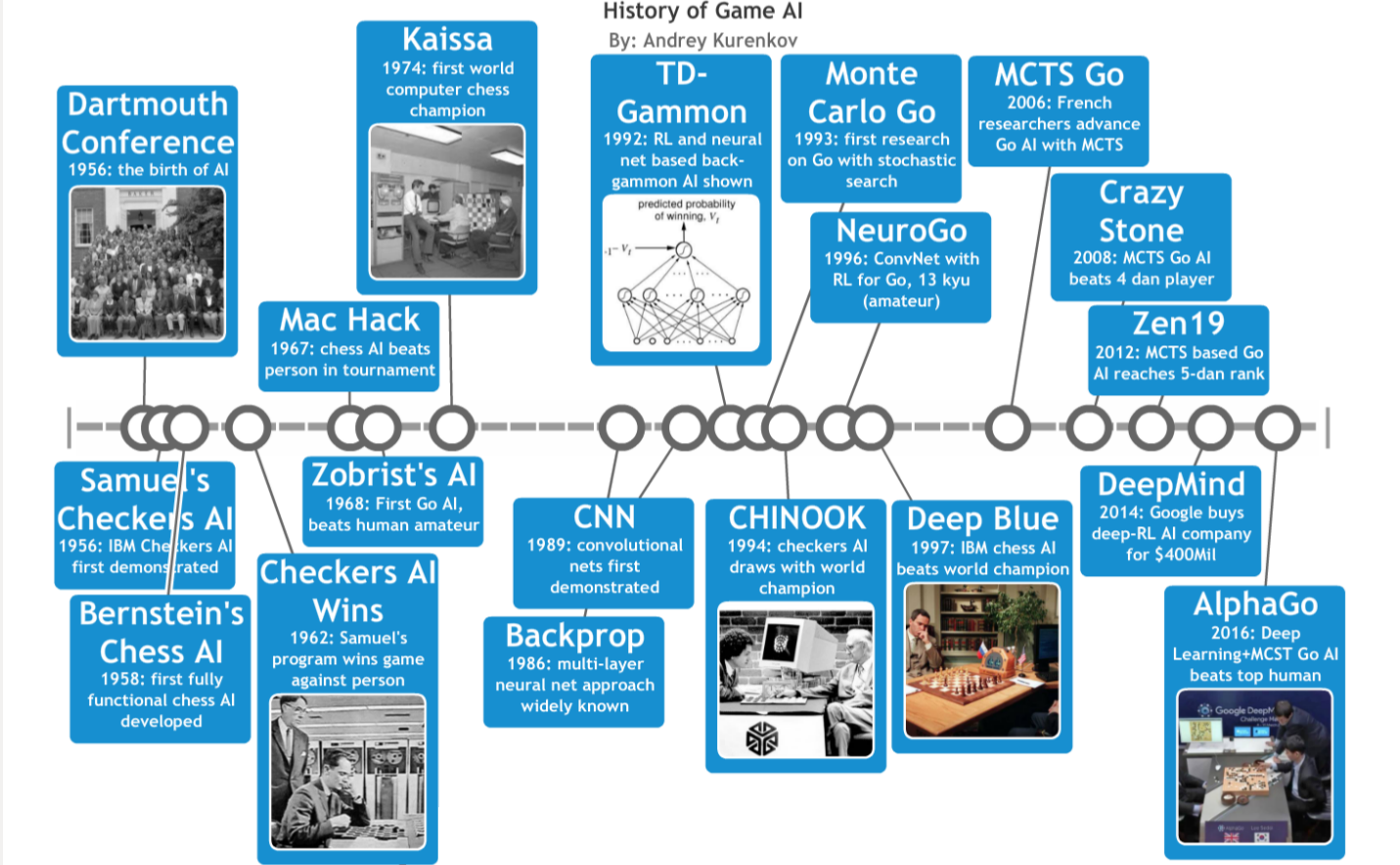

Just about the scope of this series of posts. Created with Timeline.

This is the first part of ‘A Brief History of Game AI Up to AlphaGo’. Part 2 is here and part 3 is here. In this part, we shall cover the birth of AI and the very first game-playing AI programs to run on digital computers.

Prologue: At Long Last, Algorithms Triumph Over Humans At Go

2016

On March 9th of 2016, a historic milestone for AI was reached when the Google-engineered program AlphaGo defeated the world-class Go champion Lee Sedol. Go is a two-player strategy board game like Chess, but the larger number of possible moves and difficulty of evaluation make Go the harder problem for AI. So it was a big deal when, a week and four more games against Lee Sedol later, AlphaGo was crowned the undisputed winner of their match having lost only one game. How big a deal? Media coverage accurately described AlphaGo as a “major breakthrough for AI” that achieved “one of the most sought-after milestones in the field of AI research”. Comment boards were less reserved, with many describing AlphaGo’s victory as scary or even a sign that superhuman AI was now imminent.

Months before that day, I was excitedly skimming the paper on AlphaGo after Google first announced its development 1. It struck me as a hugely impressive leap over state-of-the-art Go play, achieved through a cool combination of already successful techniques. So, when the media frenzy over AlphaGo broke out I thought to write a little post explaining why it is cool from an AI perspective, but also why it is not some scary baby-Skynet AI. In doing so, I stumbled on so many noteworthy developments and details in the 60-year history of game AI that I could not stop at writing that short little blog post. So, I hope you enjoy this ‘brief’ summary of all those exciting ideas and historic milestones that preceded AlphaGo and led to this latest marvel of human ingenuity.

As with my previous 'brief' history, I should emphasize I am not expert on the topic and just wrote it out of personal interest. I have not covered all periods or aspects of this history, so some other good resources are "The History of Computer Games", "A Short History of Computer Chess", and "History of Go-playing Programs". I am also not a professional writer, and consulted some good pieces written on the topic by professional writers such as "The Mystery of Go, the Ancient Game That Computers Still Can’t Win" by Alan Levinovitz. I also will stay away from getting too technical here, but there is a plethora of tutorials on the internet on all the major topics covered in brief by me.

Any corrections would be greatly appreciated, though I will note some omissions are intentional since I want to try and keep this 'brief' through a good mix of simple technical explanations and storytelling.

Humble Beginnings

1949

Since the inception of the modern computer, there were people pondering whether it could match — or supersede — human intelligence. And since measuring human intelligence is difficult, many of those people reasoned they could tackle the question by first making computers good at certain tasks that challenged the human intellect. So, strategy games. As early as 1949, no less than Claude Shannon published his thoughts on the topic of how a computer might be made to play Chess 2. He both justified the usefulness of solving such a problem and defined its scope:

“The chess machine is an ideal one to start with, since: (1) the problem is sharply defined both in allowed operations (the moves) and in the ultimate goal (checkmate); (2) it is neither so simple as to be trivial nor too difficult for satisfactory solution; (3) chess is generally considered to require ‘thinking’ for skillful play; a solution of this problem will force us either to admit the possibility of a mechanized thinking or to further restrict our concept of ‘thinking’; (4) the discrete structure of chess fits well into the digital nature of modern computers. … It is clear then that the problem is not that of designing a machine to play perfect chess (which is quite impractical) nor one which merely plays legal chess (which is trivial). We would like to play a skillful game, perhaps comparable to that of a good human player.”

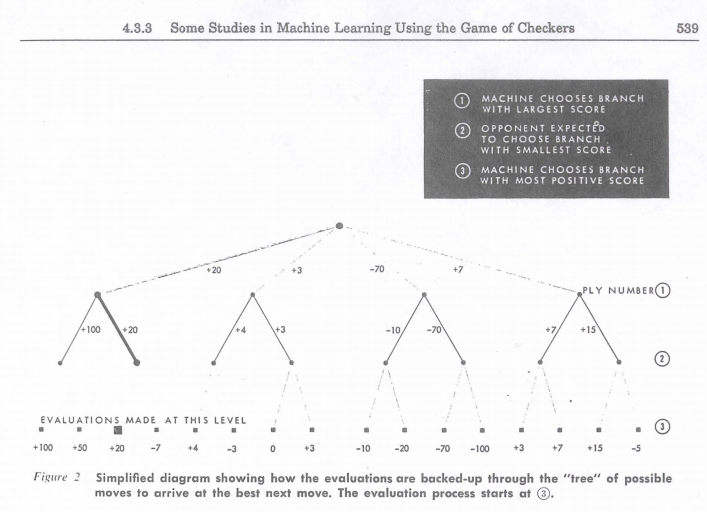

The approach Shannon suggested is today called Minimax (named after John Vonn Neuman’s minimax theorem, proven by him in 1928) and would be hugely influential for the future game-playing AIs. It is perhaps the most obvious approach one can take to making a game-playing AI. The idea is to assume both players will consider all future moves of the whole game, and so play optimally. In other words, you should always choose a move such that, even if the opponent chooses the absolute best response to that move and to every future move of yours, you will still get the highest score possible at the end of the game.

It’s easy to make a computer do this. With a representation of the positions (or states) and the rules of the game, all one needs to do is write a program to generate all possible next game states from the current state, and the possible states for those states, and so on. By doing this, the program can simulate the game past the current point and build a tree of possible paths toward the end of the game. Then, it just needs to follow the best-case path of moves to get to the best end game. This has the flaw of not capitalizing on potential mistakes the opponent might make, but on the whole is a very safe and sensible strategy.

Broken down, minimax works as follows:

1. At the start of your move, consider all the possible moves you can take.

2. For each of your possible moves, consider each of your opponent's response moves.

3. Now consider every possible response to the opponents' response, and keep thinking into the future until you reach the end of the game in your head when you can get a score.

4. Assume that just like you, the opponent can think through all the moves right through the end of the game, and so will never make a mistake — they will play optimally, and assume you will play optimally. Choose the current move to maximize your final score, assuming your opponent will always choose all future moves to minimize your score in response to whatever moves you make.

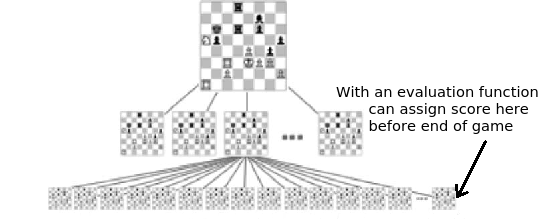

One more detail: though in theory Minimax search involves finding all paths to the end of the game, in practice this is impossible due to the combinatorial explosion of game states to keep track of with each additional move simulated into the future. That is, for every move there is some number of options (known as the branching factor) and so every additional ply (i.e. layer) in the tree roughly multiplies its size by that branching factor. If the branching factor is 10, looking one move ahead would require considering 10 game states, two moves ahead requires 10+10*10=110, three moves gets us to 1110, and so on. So, we use an evaluation function to evaluate positions that are not yet the end of the game. An evaluation function can be as simple as counting the number of pieces each player has, or much more complicated, making it possible to only search 3 or 6 moves ahead (or, a depth of 3 or 6 plies) rather than the 40-ish moves involved in the average Chess game.

Shannon’s paper defined how one could use Minimax with an evaluation function, and set the course for future work on Chess AI by proposing two possible strategies to go about it: (A) doing brute-force Minimax tree search with an evaluation function, OR (B) using a ‘plausible move generator’ rather than just the rules of the game to look at a small subset of next moves at each ply during tree search. Future Chess playing programs would often be categorized as ‘type A’ or ‘type B’ based on which strategy they were mainly based on. Shannon specifically noted the first strategy was simple but not practical since the number of states grows exponentially with each additional ply and the overall number of possible positions (the state-space) is huge. For the second strategy, Shannon took inspiration from master Chess players, who selectively consider only promising moves. However, a good ‘plausible move generator’ is not at all trivial to write, so massive-scale search as in strategy (A) is still useful. As we shall see later, Deep Blue (the program that beat Chess world champion Gary Kasparov) was basically a combination of both approaches.

1951

But, the supercomputer that powered Deep Blue was still decades away from existence, at most a dream in the minds of the early computer pioneers of the early 50s (in fact, the famous Moore’s law would not be defined until a decade later). In fact, the first Chess program was run not with silicon or vacuum tubes, nor any sort of digital computer, but rather by the gooey fleshy neurons of the human brain — that of Alan Turing, to be precise. Turing, a mathematician and pioneering AI thinker, spent years working on a Chess algorithm he completed in 1951 and called TurboChamp3.

TurboChamp was not as extensive as Shannon’s proposed systems, and very basic by future standards, but still, it could play Chess. In 1952, Turing manually executed the algorithm in what must have been an excruciatingly slow game, which the program ultimately lost. Still, Turing also published his thoughts on Chess AI and posited that in principle a program that could learn from experience and play at the level of humans ought to be completely possible4. Just a few years later, the first ever computer Chess program would be executed…

Theory Becomes Code

1956

All of this happened before AI — the field of Artificial Intelligence — was really born. This can be said to have happened at the 1956 Dartmouth Conference, a sort of month-long brainstorming session among future AI luminaries where the term “Artificial Intelligence” was coined (or so claims Wikipedia). Besides the University mathematicians and researchers in attendance (Claude Shannon among them), there were also two engineers from IBM: Nathaniel Rochester and Arthur Samuel. Nathaniel Rochester headed a small group that began a long tradition of people at IBM achieving breakthroughs in AI, with Arthur Samuel being the first.

Samuel had been thinking about Machine Learning (algorithms that enable computers to solve problems through learning rather than through hand-coded human solutions) since 1949, and was particularly focused on developing an AI that could learn to play the game of Checkers. Checkers, which has 1020 possible board positions, is simpler than Chess (1047) or Go (10250 ! We’ll get to that one in a bit…) but still complicated enough that it is not easy to master. With the slow and unwieldy computers of the time, Checkers was a good first target. Working with the resources he had at IBM, and particularly their first commercial computer (the IBM 701), Samuel developed a program that could play the game of Checkers well, the first such game-playing AI to run on a computer. He summarized his accomplishments in the seminal “Some studies in machine learning using the game of Checkers”5:

“Two machine-learning procedures have been investigated in some detail using the game of checkers. Enough work has been done to verify the fact that a computer can be programmed so that it will learn to play a better game of checkers than can be played by the person who wrote the program. Furthermore, it can learn to do this in a remarkably short period of time (8 or 10 hours of machine-playing time) when given only the rules of the game, a sense of direction, and a redundant and incomplete list of parameters which are thought to have something to do with the game, but whose correct signs and relative weights are unknown and unspecified. The principles of machine learning verified by these experiments are, of course, applicable to many other situations.”

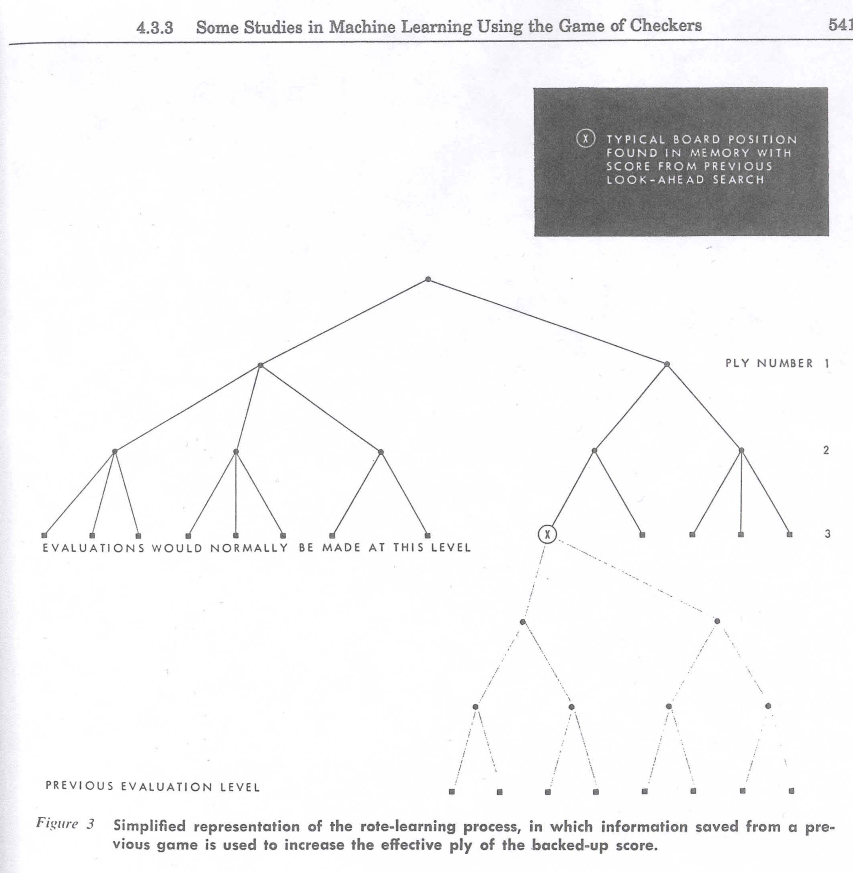

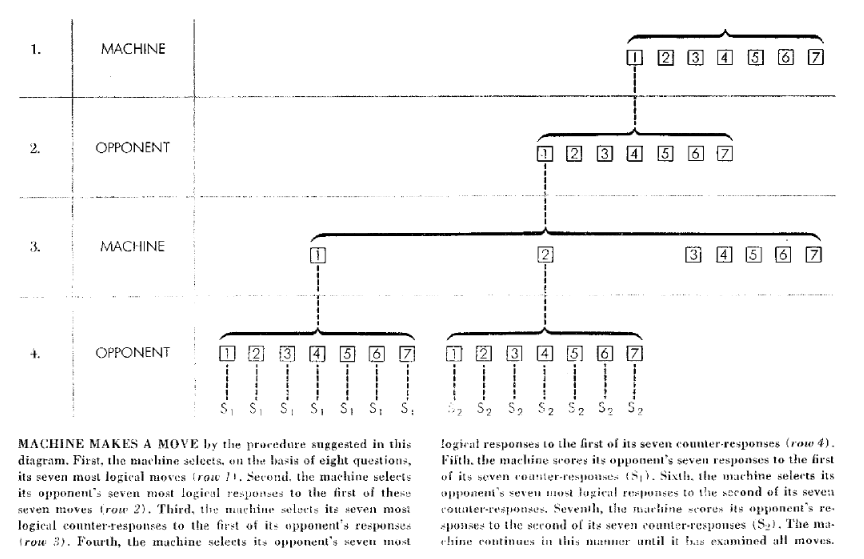

Fundamentally, the program was based on Minimax, but had an additional hugely important aspect: learning. The program became better over time without human intervention, through two novel methods: (A) “rote-learning”,— meaning it could store the values of certain positions as previously evaluated with Minimax, and so not need to spend computational resources considering moves further down those branches — and (B) “learning-by-generalization”, i.e. modifying the multipliers for different parameters (thus modifying the evaluation function) based on previous games played by the program. The multipliers were changed so as to lower the difference between the calculated goodness of a given board position (according to the evaluation function) and its actual goodness (found through playing out the game to completion).

Rote learning was a fairly obvious way to make the program more efficient and capable over time, and it worked well. But it was learning-by-generalization that was particularly groundbreaking, as it showed that a program could learn to ‘intuitively’ know how good a game position was without tons of simulation of future moves. Not only that, but the program was made to learn by playing past versions of itself, which would one day be a key component of AlphaGo! But let’s not get ahead of ourselves…

Here is a fun excerpt from the paper about the advantages of each learning strategy:

"Some interesting comparisons can be made between the playing style developed by the learning-by-generalization program and that developed by the earlier rote-learning procedure. The program with rote learning soon learned to imitate master play during the opening moves. It was always quite poor during the middle game, but it easily learned how to avoid most of the obvious traps during end-game play and could usually drive on toward a win when left with a piece advantage. The program with the generalization procedure has never learned to play in a conventional manner and its openings are apt to be weak. On the other hand, it soon learned to play a good middle game, and with a piece advantage it usually polishes off its opponent in short order.

Apparently, rote learning is of the greatest help, either under conditions when the result of any specific action are long delayed, or in those situations where highly specialized techniques are required. Contrasting with this, the generalization procedure is most helpful in situations in which the available permutations of conditions are large in number and when the consequences of any specific action are not long delayed."

Not only were these ideas groundbreaking, but they also worked in practice: The program could play a respectable game of Checkers, which was no small feat given the limited computing power at the time. And so, as this great retrospective details, when Samuel’s program was first demonstrated in the very early days of AI (in the same year as the Dartmouth Conference, in fact) it made a strong impression:

“It didn’t take long before Samuel had a program that played a respectable game of checkers, capable of easily defeating novice players. It was first publicly demonstrated on television on February 24, 1956. Thomas Watson, President of IBM, arranged for the program to be exhibited to shareholders. He predicted that it would result in a fifteen-point rise in the price of IBM stock. It did.”

1957

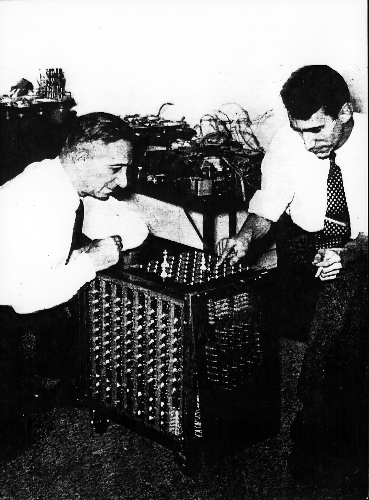

But, this is Checkers — what of the game everyone really cared about, Chess? Well, once again it was employees at IBM who pioneered the first Chess AI, and as with Samuel those employees were supervised by Nathaniel Rochester. The work was chiefly led by Alex Bernstein, a mathematician and experienced Chess player. Like Samuel, he decided to explore the problem out of personal interest and ultimately led the implementation of a fully functional Chess playing AI on the IBM 701, which was completed in 1957 6. The program also used Minimax, but lacked any learning capability and was constrained to look at most 4 moves ahead, and consider only 7 options per move. Until the 70s, most Chess-playing programs would be similarly constrained, plus perhaps some extra logic to choose which moves to simulate, rather like the type (B) strategy outlined by Shannon in 1949. Bernstein’s program had some heuristics (cheap to compute ‘rules of thumb’) to select the best 7 moves to simulate, which in itself was a new contribution. Still, these limitations meant the program only achieved very basic Chess play.

Still, it was the first fully functional Chess-playing program and demonstrated that even extremely limited Minimax search with a simple evaluation function and no learning can yield passable novice Chess play. And this was in 1957! So much more is yet to come in the coming decades…

Acknowledgements

Big thanks to Abi See, Pavel Komarov, and Stefeno Fenu for helping to edit this.

References

-

David Silver, Aja Huang, Christopher J. Maddison, Arthur Guez, Laurent Sifre, George van den Driessche, Julian Schrittwieser, Ioannis Antonoglou, Veda Panneershelvam, Marc Lanctot, Sander Dieleman, Dominik Grewe, John Nham, Nal Kalchbrenner, Ilya Sutskever, Timothy Lillicrap, Madeleine Leach, Koray Kavukcuoglu, Thore Graepel & Demis Hassabis (2016). Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature, 529, 484-503. ↩

-

Shannon, C. E. (1988). Programming a computer for playing chess (pp. 2-13). Springer New York. ↩

-

A Jenery (2008). A Short History of Computer Chess. chess.com link ↩

-

Alan Turing (1953). Chess. part of the collection Digital Computers Applied to Games. in Bertram Vivian Bowden (editor), Faster Than Thought, a symposium on digital computing machines, reprinted 1988 in Computer Chess Compendium ↩

-

Samuel, A. L. (1959). Some studies in machine learning using the game of checkers. IBM Journal of research and development, 3(3), 210-229. ↩

-

Bernstein, A., & Roberts, M. D. V. (1958). Computer v chess-player. Scientific American, 198(6), 96-105. ↩

Previous Post | Next Post

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.